[size=1.45em]49ers lose a member of their family[/size]

By Scott Fowler

September 14, 1999

The world is a little bleaker this morning.

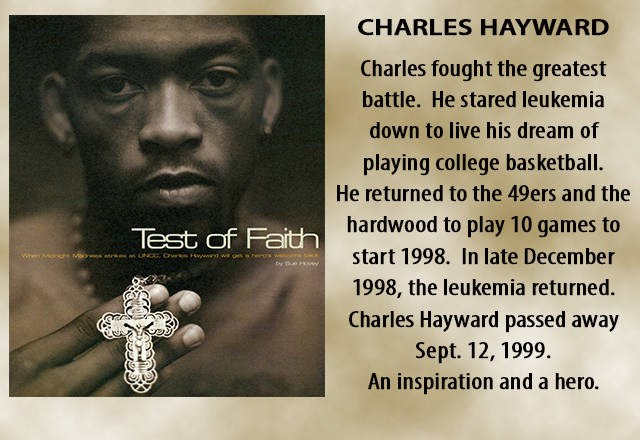

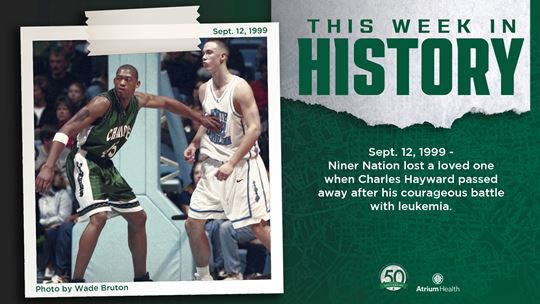

Charles Hayward is no longer with us, and that isn’t fair. No 21-year-old man should die of leukemia. No family should have to go through what the Haywards have. No university should have to plan a campus memorial service for one of its athletes.

But life has claws and they tear at our hearts this morning as we remember Charles Hayward – a quiet, dignified soul who once had the possibility of becoming one of the best basketball players in UNC Charlotte history.

It is important how we remember Charles Hayward. It is more important where we remember him – on the basketball court.

It is fitting that Hayward’s memorial service Wednesday will be held at UNCC’s home arena. Hayward’s love for his sport was uncomplicated – he felt most at home in a gym.

Hayward was always comfortable thinking of himself as an athlete, ever since he first dunked a basketball in the fifth grade in Louisiana. He was never comfortable being known purely as ``the player with leukemia.’’

All Charles wanted to do was play ball,'' said Galen Young, a teammate of Hayward's at UNCC.That was his thing.’’

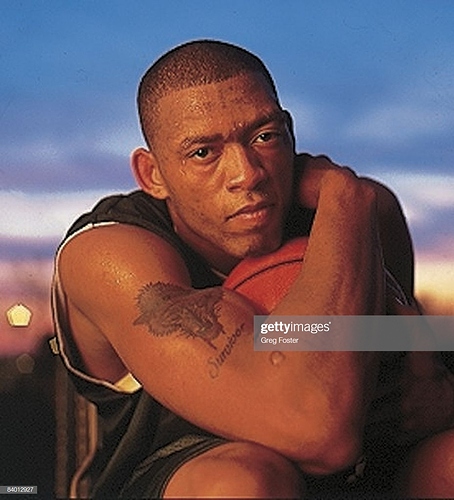

A willowy 6-foot-8 forward, Hayward had long arms that gave him the reach of a 7-footer. He didn’t bat away every shot that came down the lane, but he sure scared off a lot of them.

Hayward in the air, long arms reaching toward the sky, was a block waiting to happen.

While his leukemia was in remission, Hayward started three times last season. He blocked six shots in one game.

Charles played in just 10 games,'' Young said.But he had so many blocks that it took (center) Kelvin Price almost all season to catch him for the team lead.’’

Hayward was a basketball star growing up in Alexandria, La. His coach, Charles Smith, had him play center, because Smith didn’t have anyone else as tall as Hayward. But Smith also allowed him to step out and shoot three-pointers, and the coach watched in awe when Hayward sometimes outran the guards on the fastbreak.

``He could do anything,’’ Smith said once.

Hayward was following the path of his older brother Eric in high school. Eric became a fine role player for Connecticut. His specialty was drawing charges; he took 43 of them in three seasons.

Eric tried to take charge No. 44 for his younger brother. When Charles had a relapse and desperately needed a successful bone-marrow transplant, Eric became the donor. That was in April.

Charles Hayward’s mother, Janice Harrell, was with her son almost every day for the past two years. Once Charles was diagnosed with leukemia in October 1997, she quickly moved from Louisiana to North Carolina to stay with him. Eric came, too.

When Charles wasn’t in the hospital, the three of them shared two rooms at a motel near the UNCC campus. The family went to Chapel Hill for the bone-marrow transplant in April.

Charles Hayward never got to come back to Charlotte.

He moved out of the Chapel Hill hospital into a nearby apartment briefly, but had to return to the hospital when his body started rejecting his brother’s bone marrow.

Six days ago, UNCC athletics director Judy Rose came across some notes she had made eight months before – a ``crisis plan’’ that specified all of the ways the university would try to help the Haywards if Charles died.

``Thank goodness we’ve never needed to use this,’’ Rose thought to herself.

The next day, Rose was told Hayward probably wouldn’t live through the weekend.

Hayward had already told his relatives he didn’t want to be placed on a life-support system if it came to that. He slipped out of consciousness Saturday and died Sunday night at 10:45.

It is difficult now, with the death so fresh and the pain so intense.

But when we remember Charles, we shouldn’t remember needles or chemotherapy.

We should remember him in full leap – as the player who tried to block every shot and swatted away leukemia as many times as he could.

Let us think of him the way he would want us to.

Soaring up into the sky, one last time.